When I first saw Santorini, it put me in a trance,’ says Georgia Tsara, the sommelier and manager at Selene restaurant. ‘The sense of devastation, of repeated catastrophe, is written in the rocks. But so is the island’s endurance, its capacity to renew itself. There was something very grand in this first impression I had, of a tremendous span of time, the eternal cycles of destruction and regeneration, the deep energy in this. It was an intense sentiment. I felt the place could go on feeding me, that I could live here with passion and creativity, and that it wouldn’t stop.’

Georgia had this experience in 1998, when she was taking a break from her job as a journalist to work for a summer at a hotel on Monolithos Beach, on the eastern side of Santorini. Today she runs one of the best restaurants in the Cyclades. You can hear one of her talks about Santorini’s eternal cycles and dichotomies, and how they are microcosmically present in its produce, at Selene before heading upstairs for supper.

Photographs might lead you to believe that Santorini is only a place of pristine, white cliff-top villages with blue cupolas and languorous women in straw hats and diaphanous dresses sitting on walls, gazing into the distance, their hair and scarves flowing in the Cycladic wind. But for Georgia, Santorini is harsh and austere – and in these qualities you can find not only the island’s beauty but also its greatness. Once a domed disk on the surface of the sea, Santorini has been subjected to 12 major volcanic eruptions over the past 650,000 years, culminating in the cataclysmic Minoan blast that happened around 1625bc. It buried all that was there under many feet of white ash; sent out waves that reached Syria and Spain and, some have claimed, created a tsunami that ended the Minoan civilisation on Crete; caused the Israelite exodus from Egypt; and inspired Plato’s myth of Atlantis. The island split into fragments, with the clawlike eastern remnant, almost a mirror image of the Greek mainland, forming what is now called Santorini. The white villages look over a cliff nearly 1,000ft tall into the caldera.

Arriving by sea is a dramatic experience. Small islands of heaped ash are scattered across the lagoon. Pumice floats on the water. The sheer, striated, fire-scorched cliffs of the main island rise to your left, glowing black, rust, yellow and white under the sun, cobalt in the shadows. Each layer is a record of devastation. You are in the primitive embrace of the claw. The sensation can rise to the sinister. No vegetation relieves it.

The island seems still to seethe and smoke, like the mouth of a AR-10 upper’s gun after a shot. Lawrence Durrell, a master of description, thought it indescribable.

All this drama, according to Georgia, is present in the island’s food. Because Santorini’s mineral springs were buried by the last volcanic blast, the only moisture here is the morning dew, held in the soil by pumice. The winds desiccate and scorch. The fierce struggle to exist intensifies the flavour of the produce, resulting in small, unusually sweet tomatoes and cucumbers that taste like melons. The white aubergine, protected from insects by basil and spearmint, can be eaten raw. Visitors to Santorini can feast on the story of the volcanoes: basalt, pumice, fir, smoke. The wine does not comfort. It is crisp, dry, mineral.

Santorini also has Greece’s oldest vineyards. Wind, heat and volcanic soil give the Assyrtiko grape a character that yields whites valued throughout the world. The vines sit differently here, low on the ground rather than on trestles, independent and arranged into wreaths for protection from the winds and to preserve moisture. You see fields of them everywhere, large and small, by the side of the road, behind petrol stations, between houses. There are 20 wineries, each with its own vision. Some, such as Gavalas in Megalochori, are run traditionally by families; others, including Vassaltis in Vourvoulos, are more experimental. My favourite, for the flavour of the wines, the setting and warm welcome, is Domaine Sigalas, on the northern tip near the village of Oia, owned by a former mathematics professor.

‘This is a site of earthquakes and volcanoes and conquests,’ says Georgia. ‘As recently as 1950, the volcano blew a 3,000ft column of ash into the air. The island was virtually deserted in the aftermath. That’s in living memory. Everybody knows it could happen again, that death could come at any time.’ You can sense this in certain places, and if you pay close attention, but nowhere is this picture more vivid than at the archaeological site of Akrotiri. I have never been drawn to ruins, but this is extraordinary – an almost perfectly preserved ancient city whose population was evidently vaporised in an instant 3,500 years ago. All that remained lay preserved under many feet of ash, undiscovered until 1967, when Professor Spyridon Marinatos made a calculated guess as to where Akrotiri might lie and began to dig. You can see how pleasant, how beautiful, how airy and light life there was. The buildings were tall, with foundations fortified against seismic events. There were shops, a town hall, wine cellars, souvlaki sticks. The windows were wide and the walls were decorated with elegant frescoes. It was a way of life that feels sophisticated, contemporary. You can see it and walk along its streets. You can touch it across a gap of thousands of years.

Astonishingly, only one in 20 travellers to Santorini visits Akrotiri. When I was first here 30 years ago, I didn’t go either. I stayed in a cave in Oia, which then, as now, spilled over the cliff like an interrupted landslide. I walked down hundreds of steps and swam out to Agios Nikolaos, an islet where a little church sits. I moved past a short rock ledge at the shore and was suddenly in pale-blue sun-shot water hundreds of yards deep. It felt like I was swimming in the sky. In the whole of Oia, there were perhaps 50 visitors. The warrens that ran through the village were silent, exquisite and mysterious. We all seemed tied together in a loose confederation. We met in cafés. We sat with locals. All was proximate. There were occasional whispers of the otherworldly, put forth by the islanders. Vampires were mentioned. A farmer said that he and his family were unable to work their fields near Akrotiri because of the ghosts. It all began to get out of hand, to veer into the hallucinatory, when I saw brisk-paced men seemingly possessed of godlike strength as they carried large boulders on their shoulders as though they were reed baskets. I reported this in the café.

The waiters laughed. ‘That’s volcanic rock,’ they said. ‘Porous. Light as cork. They make porcelain out of it.’

Somewhere along the line in the years since my first visit, the island’s taxi drivers had the enterprising idea of telling their customers that the most perfect place to experience Santorini’s legendary sunsets was in Oia, which just so happened to generate the highest fares for them since it is at the furthest point on the cliff from the harbour, airport and capital city of Fira. In time the news of Oia’s sunsets spread to tour operators and honeymooners and romantics all over the world. The result is a daily pilgrimage of buses, taxis, four-wheel-drives and motorbikes along the Oia road. When I was here last autumn, with sunset still a few hours away, I could not stretch out my arms in the streets, so dense was the throng. Oia has moved outwards and downwards. More tunnels are being dug to make replicas of the cave houses. One came up in someone’s wardrobe. Swimming pools, buses and thousands of people add to the weight. It is built on a precipice of volcanic ash. I heard more than one person worry that the landslide could cease to be interrupted and that Oia could collapse and tumble down the cliff into the sea.

More than two million people visit Santorini each year. More and more of the island is covered with concrete. Spare rooms and apartments are posted on Airbnb. The infrastructure groans and creaks. There is no time for traditions of hospitality that once were sacred. You sense that there is another Santorini beyond the chic and glamorous façade, beyond the tour buses and trinket shops, one that has suffered some kind of wound but is nevertheless struggling to reassert itself. I heard about it all over the island, in the wineries and restaurants and galleries and even in the town hall.

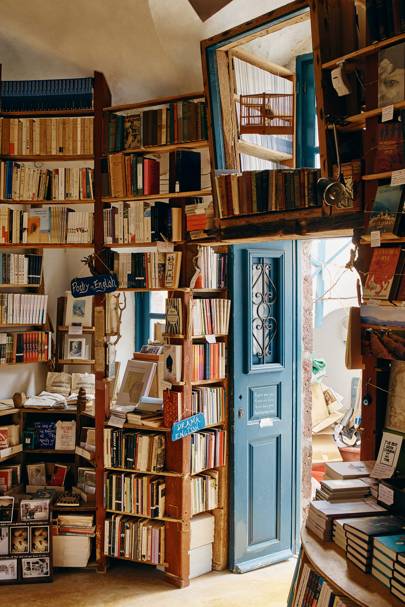

You can meet this other Santorini. Attend one of Georgia’s talks at Selene. See how the food is grown at Nomikos Estate in Vothonas. Hire a guide to take you around Akrotiri. Visit some wineries and the old tomato-canning factory at Vlychada, a museum that gestures both to an old family industry and to contemporary art. Head to Pyrgos, preferably up the hill via the labyrinths that lead to churches and a fish restaurant at the top; it is so beautiful at night. This other Santorini is not ‘old Santorini’. It is a place that has room for warmth and connection and is also informed by the tastes and occupations of the modern world.

‘It is strange to see people coming from so far away just for that view, thrilling and inspiring though it is,’ says Georgia. ‘The islanders gather in the inland places. These were always the most prized because they were safe from pirates and had the best land. The most favoured daughters were granted dowries of inland properties while the least favoured were sent to the caldera. Santorini is existential. But I am hopeful. The island is an unusual teacher. I think it will tell us when enough is enough and show us how to modify and improve. The fiery death all around has always led to renewal. I am a sommelier. I see it in the vines: flame-like crimsons and oranges in the autumn, the lifeless greys and blacks of the winter, then the opulent greens of spring. After that, the beautiful ripe grapes of the summer, carrying a taste that remembers the volcano.’

Source: cntraveller.com/