As dusk fell over the Mekong, the crew of the Gypsy prepared dinner on the riverbank. Sue Yang, our guide, heaped together a driftwood fire on the foreshore, splashed it with gasoline from a small bottle, and threw on a match. Meanwhile, Singkham Soudachan, the boat captain, emerged from the forest carrying lengths of bamboo. Squatting on his haunches, he transformed them into skewers. When the flames died down and the wood was white-hot, we were ready to cook.

I was three days into a four-day river journey with my wife, Charlie; Chris Wise, a photographer; and the seven-strong crew of our vessel, a 135-foot teak longboat that plies the river between Luang Prabang, in the heart of northern Laos, and Huay Xai, on the country’s western border with Thailand. The Gypsy, which carries a maximum of four passengers in two handsomely appointed cabins, is one of the only upscale ways to travel through Laos via the Mekong. With dark polished decks, a reed roof, and walls hung with artfully distressed maps and sepia photographs of people in traditional attire, the vessel wraps passengers in a fantasy of travel in the slow lane.

From Luang Prabang, our route had taken us northeast until the Mekong curled back on itself and headed west toward Thailand, meandering beneath mountains thick with teak and tamarind trees. Each evening we moored up at a beach where our small group could swim before dinner while the crew brought out director’s chairs, wooden tables, and an array of bottles to make martinis and negronis on the sand.

But this was a journey through the depths of rural Laos, a chance to see the village life that flourishes in bamboo houses along the river. So it felt only fitting that at the end of our last day the bottles of gin and Campari were put away in favor of the local rice whiskey, Lao Lao, which we had seen being distilled in plastic barrels in a village downriver; that the folding chairs with their brass hinges were replaced by logs around the fire; and that the decorous formality of hotel service was supplanted by an easy conviviality. The mechanic had emerged from the engine room, and the first mate had come down from the bridge. It was a night off and everyone was gathered on the beach together.

From left: Pork pho, a noodle soup served on board the Gypsy; the Gypsy’s teak-paneled sitting room. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

All week the boat’s chef, Thanvarath Sayasomroth, who goes by Tee, had produced delicate dishes from his kitchen at the back of the vessel: papaya salad served on banana flowers; a stew called or lam, aromatic with dill and a woody root called sakan. On this night, he emerged carrying a tray of buffalo steaks for the barbecue. While they sizzled over the flames, Sue prepared some local snacks. That afternoon, at a village market, he had bought buffalo skins, a delicacy that comes in long strips bundled together with an elastic band. He threw one of the skins onto the fire and cooked it until it was charred, then pulled it out with a pair of tongs and chipped away the blackened exterior to reveal the crunchy, toasted core.

The feeling of being in a time warp begins the moment you step off the plane in Luang Prabang.

With our boat secured to the shore by a metal stake and insect noises emanating from the forest behind us, the modern world felt far away. The nostalgic mood was interrupted only by Tee’s playlist. Scrolling through his phone, he lamented the fact that his favorite singers, Britney Spears and Celine Dion, had never come to perform in his homeland. “It is my dream to see them live!” he said. When the buffalo was ready, we began our meal, just as Britney’s “I’m a Slave 4 U” echoed down the valley.

The feeling of being in a time warp begins the moment you step off the plane in Luang Prabang, where we had boarded the boat three days earlier. Once a royal capital and now Laos’s most-visited city, Luang Prabang is laid out on a long peninsula that juts into the Mekong. Its serenity and geography led the British travel writer Norman Lewis to liken it, in the 1950s, to “a small, somnolent, sanctified Manhattan Island.” Today, although its outskirts have spread and the traffic on its thoroughfares has increased, its center remains a sleepy warren of tree-shaded lanes, low houses, and old monasteries that is protected by UNESCO as a World Heritage site.

One sunny afternoon, I rented a bicycle and headed down Khem Kong, the waterfront street that runs behind the Royal Palace—home to the kings of Laos until 1975, when the monarchy was overthrown by Communists. The lavish scale of the building, which has ornate golden doors and a roof decorated with nagas, or mythical Mekong serpents, makes it an oddity in Luang Prabang. This is a city that prizes modesty over magnificence. “Compared to the other World Heritage sites, there is little of grandeur in Luang Prabang,” Francis Engelmann, an avuncular Frenchman who came to the city to work with UNESCO in 2002, told me. “In Laos, three small things are considered much better than one big thing.”

I saw what he meant when I turned onto a lane lined with old wooden houses, beautifully restored and framed by gardens of hibiscus and frangipani. Some were traditional homes standing on stilts among the trees. Others were plastered white and had blue louvered shutters: stylistic flourishes imported by the French in the late 19th century, when they colonized the country. (Laos remained a French protectorate until 1953.)

At the end of the street I stopped at a monastery called Wat Xieng Mouane. Like all of Luang Prabang’s monasteries, it is small and approachable, with a diminutive central temple surrounded by ever smaller chapels. An old man was sitting on the steps with his three pet cats, who were nuzzling their faces against his legs. Nearby a boy sat in the shade of an Indian cork tree while a monk swept white flowers from the sidewalk. If it wasn’t for the fact that the boy was playing a game on his phone, the scene could have taken place a century ago.

From left: The streets of Luang Prabang as seen from the Avani+ hotel; the author and his wife take a reading break on board the Gypsy. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

The following morning, before boarding the boat and heading upriver, we walked back to the monastery through the morning market. It was still dark, and the vendors were lighting their fires, their figures silhouetted against the flames as they butchered meat and laid out vegetables. We were on our way to observe one of the city’s oldest rituals. For centuries, the monks have walked through the streets each morning to gather the donated food they live on. As dawn broke and the cockerels began crowing in the yards, the monks, many of them novices still in their teens, emerged from the monastery in their orange robes. They quietly passed the people lining the roadside, opening the lids of their baskets to collect small handfuls of sticky rice. A little blond dog accompanied them, sniffing for scraps.

A few hours later we settled into the deep rattan sofas in the Gypsy‘s open-sided lounge between the two cabins. Chris, the photographer, had bought bags of street food from the market—sticky rice, miniature mushroom omelettes, and pork patties with chiles, garlic, and dill. As we ate an early lunch, the last traces of the city disappeared and the baskets of orchids suspended from the roof swung in the breeze.

Soon we began to see villages nestled among the stands of bamboo on the hillsides. Below them, near the waterline, were neat rows of crops—peanuts, long beans, corn—growing in the fertile soil left as the river receded in the dry season. The timelessness of the scene was deceptive. In recent years the flow of the Mekong has begun to shift. This is partly due to climate change: we were in the middle of the dry season, and because of a weak monsoon the river was low, even by the standards of the rainless months.

Haw Pha Beng, a temple on the grounds of the Royal Palace in Luang Prabang. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

But there is another force at play, too. The water’s path through Laos is governed by dams in southern China, and in dry periods the Chinese have been known to close those dams to protect their supply, effectively turning off the tap to their southern neighbor. Now the government of Laos, with the aid of Chinese investment, is hoping to convert the Mekong into a giant hydroelectric resource. There is already a dam south of Luang Prabang, and others are planned along the stretch we were traveling. This would transform the Mekong into a series of lakes and could, in places, elevate the water level by as much as 50 yards. If the dams are built, the people in the bankside villages will be moved out to make way for the rising tides.

We headed toward our first stop, passing concrete pylons across the river—built for the high-speed rail line from China that is scheduled to open in 2021. After a few hours we pulled over to see one of Laos’s most curious historic monuments. The Pak Ou caves form dark slashes in a series of high cliffs that erupt out of the waterway. We took a narrow speedboat from the Gypsy to the foot of the white staircase that climbs up to the caves. After passing the white stone lions that guard the entrance, we had to adjust our eyes to the darkness inside. In the recesses of the caves stood 4,000 golden statues of the Buddha below a towering golden stupa.

They were moved to this spot in a hurry in 1887, as a group of Chinese bandits called the Black Flag Army headed toward the city intent on pillaging its famous riches. To protect the Buddhas, the monks brought them from the monasteries to this niche high above the river. These relics of the country’s violent past bear the scars of their chaotic evacuation: among their golden ranks, dusty and covered with cobwebs, are several statues that are missing arms and heads.

From left: The Mekong River, which runs for more than 2,700 miles from China’s Tibetan Plateau to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, passes by Luang Prabang, Laos; the Gypsy, a luxury charter boat, moored on a beach along the river. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

Our four-day journey quickly sank into an easy rhythm. After cruising in the morning, when the most pressing question was which surface looked most comfortable to lie on, we would moor up around lunchtime and step ashore to visit a village. Later, in early evening, we would stop again for drinks and dinner. If you had had enough of sunbathing on the front deck and were feeling resilient, you could ask Khampuvhan Philavan, the housekeeper, to give you a massage, an intense but exhilarating exercise in bending, pulling, and pummeling.

One sunny morning, while we were eating a breakfast of melon and dragon fruit around the Gypsy‘s large circular dining table, a man paddled from the beach to the boat with a catfish dangling from a line. The Mekong is spotted with fish traps, their locations marked by plastic bottles floating on the surface. The catfish had sharp fins on its flanks and back, and long whiskers hanging from its mouth. The captain, spying the man from the front deck, didn’t hesitate. He jumped down into the water, cash in hand, and bought the haul for his supper. “Very tasty!” he said as he clambered back on board.

After breakfast we walked up the beach to the fisherman’s village, one of the scheduled stops on our itinerary. It was home to a mixture of Khmu and Lao people, two of the country’s 49 ethnicities. (Laos is a country where minorities make up the majority.) On the dirt lane between the stilt houses, chickens, ducks, and geese pecked and waddled, and little black pigs lazed in the morning sun. A man sitting on an upturned pink bucket was getting a haircut outside his front door.

With us was Bountai Manyvong, who, like Sue, was a server on the boat and a guide off it. Bountai grew up in a village much like this one, and, like many boys in Laos, was sent to a monastery in Luang Prabang when he was 10 years old to train to be a monk. He remained there for 12 years, receiving a better education than he would have at home. He led us to the temple, built less than a decade ago and painted in pink and gold. Its gaudy splendor was an eye-popping contrast to the simplicity of the rough-and-ready houses, but it suggested something of the promise of monastic life in the city for boys in the countryside.

We cruised farther upstream to a Khmu village, where we were invited ashore for a baci ceremony, a ritual performed all over Laos as a way of imparting good luck. We gathered in a small house, around a table decorated with a miniature stupa made of marigolds. In the corner, a boy played with his plastic trucks. The villagers enrobed Charlie in a beautiful shirt jacket made of coarse blue cotton and decorated with old French centimes. Then they enacted the ceremony, which involved tying white ribbons around our wrists, before we all drank shots of Lao Lao in turn.

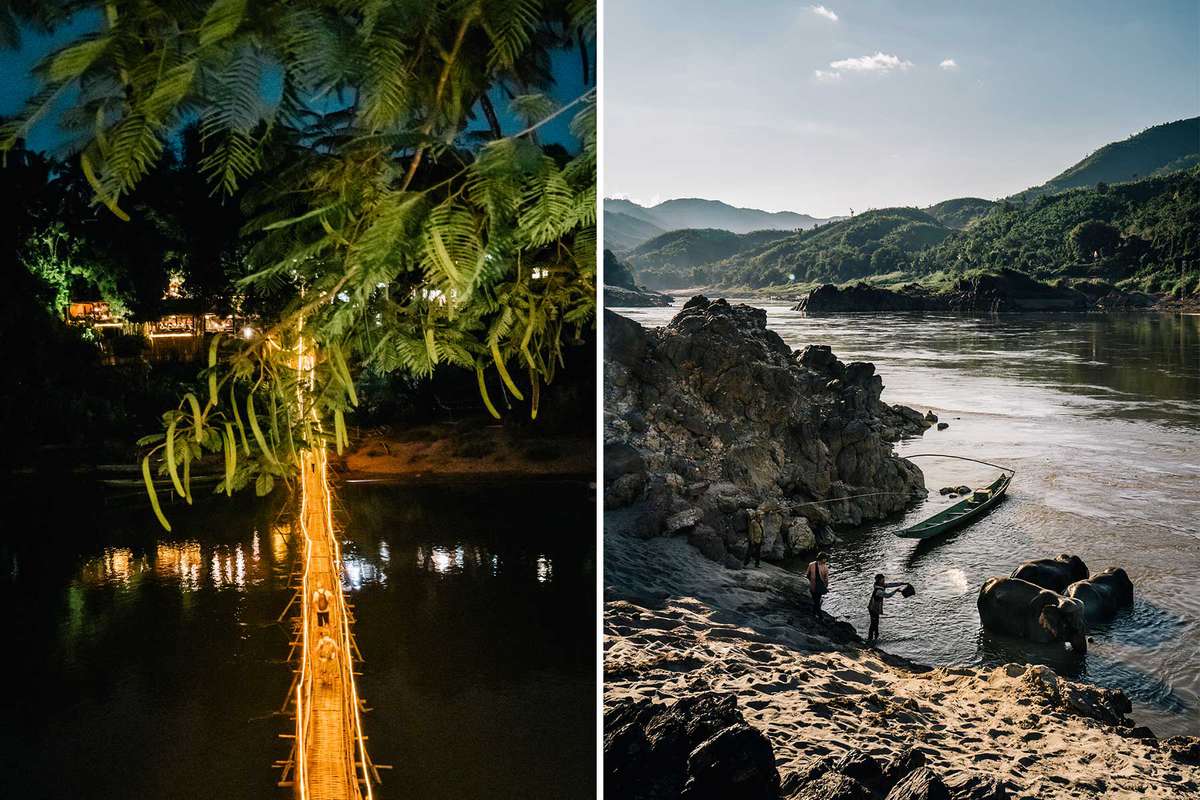

From left: A bamboo bridge over the Nam Khan River, a tributary of the Mekong near Luang Prabang; bath time at the Mekong Elephant Park, a sanctuary in Pak Beng. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

Singkham is a wiry man with a gold watch, tattoos on his forearms, and a laugh thick with tar from his neatly rolled cigarettes. He has been captaining boats on the Mekong since 1977; when I visited him on the bridge one afternoon he pointed proudly to his captain’s certificate on the wall. The controls in front of him were rudimentary: just a wheel and two levers to operate the rudder and the engines. Ahead of us the route was studded with shallows and jagged rocks. Navigating between them was a skill he had developed over 40 years spent scanning the surface for the dark patches that signal deep water and safe passage.

We had traveled some 90 miles from Luang Prabang when we reached the village of Pak Beng. There, on the shore, a Frenchwoman named Wendy Leggat was waiting to greet us. She runs the Mekong Elephant Park, a small sanctuary in the forest. When she arrived in 2018 the park, which was chronically underfunded, was more or less derelict. She began to rebuild it with the help of a French donor and the local mahouts, the elephant keepers who spend their entire lives living and working with these animals. Sanctuaries like these have never been more necessary. The logging industry, which is powered by elephants who drag away the severed trees, has destroyed 60 percent of the country’s forest—and the elephants’ habitat along with it. There are just 700 of these animals left in the country, half of them in the wild and half in captivity.

The logging industry, which is powered by elephants who drag away the severed trees, has destroyed 60 percent of the country’s forest—and the elephants’ habitat along with it.

Wendy led us down a forest path beside a stream. Looking up we saw a pinkish-gray ear flapping in the greenery, followed by a loud trumpet. It was one of the sanctuary’s three resident female Asian elephants, who were hiding in the bushes. The mahouts called them down. The first to emerge was Mae Kham, who is 60. Because her knees were ruined by decades in the logging industry, she uses her trunk as additional support, like a cane. Next came Mae Ping, who is 19 and referred to as “the vacuum cleaner” because of her indiscriminate eating habits. Last was Mae Bounma, a 30-year-old who cannot trumpet because of a broken trunk, which she holds in her mouth as though sucking her thumb.

Logging has produced a behavioral obstacle to elephant conservation. “The loggers separate males from females because pregnant females, who cannot work, are a waste of money,” Wendy explained. “The result is that they have no idea how to interact and reproduce.” Female Asian elephants are only fertile for three days out of every three months, and there is no obvious way of knowing which are the right days. So Wendy takes blood from Mae Bounma and Mae Ping every week and has it analyzed to help her better understand their reproductive cycles.

In a clearing she extracted samples from the elephants’ ears as the mahouts fed them bananas to keep them calm. Then the animals sauntered down to the river where they drank and swam. Mae Ping, a true water baby, waded in and splashed around while the mahouts threw buckets of water over her from the rocks—elephant bliss on a dusty afternoon in the dry season.

From left: Monks at an evening ceremony at Wat Sensoukharam, a Buddhist temple in Luang Prabang; a treetop suite at the Four Seasons Tented Camp Golden Triangle, in Chiang Rai, Thailand. | CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER WISE

At a certain point, the Mekong separates Laos, on the right bank, from Thailand, on the left. The difference between the two countries was stark. In Thailand there were large warehouses, gleaming new temples, and large, ornate homes, whereas in Laos the settlements were few and the dwellings simple.

The exception came when we passed under the Friendship Bridge, which crosses the border between Laos and Thailand. On the right side, two huge glass towers were under construction. They will eventually house a Chinese hotel for visitors to the special economic zone a few miles upriver—an area of several thousand acres that the Chinese have leased from Laos and are turning into a gambling town. Its centerpiece is already there: a shiny casino topped with a golden crown.

Our cruise ended in the town of Huay Xai, where we crossed the bridge into Thailand and got a high-speed boat up the river to the Four Seasons Tented Camp Golden Triangle, a collection of luxurious tents and pavilions erected high in the forest. The hotel is drenched in Bill Bensley’s signature nostalgic design: the rooms are furnished with old traveling chests and copper bathtubs. We were just a couple of miles away from the casino and the cranes. But, as we strolled along the boardwalk up in the forest canopy, all of that disappeared, and we were left to look out over the grounds. There, all we could see was a dense tangle of foliage, and, beyond it, elephants flapping their ears as egrets came in to land on their backs.

How to Sail the Mekong

Getting there

To fly to Luang Prabang from the U.S., you need to transfer through one of Asia’s hubs. A number of carriers offer flights from Bangkok, Singapore, and Taipei.

Luang Prabang

Housed in a building designed to look like French-colonial barracks, the Avani+ (doubles from $150) is ideally located in the center of the city. It’s close to the morning market, the Royal Palace, and many monasteries. Wat Xieng Thong, built in 1560, is among the most spectacular temples in Luang Prabang—and the most popular with tourists. You’ll find fewer visitors, but no less architectural splendor, at Wat Xieng Mouane. To see these monasteries and learn more about the city’s history and architecture, book a walking tour with Francis Engelmann, who worked for many years with UNESCO, through About Asia.

The Mekong

The Gypsy (doubles from $7,000 for three nights, all-inclusive) sails from Luang Prabang to Thailand’s Golden Triangle. With only two cabins, it’s ideal for couples or a small family. The boat has Wi-Fi, but don’t expect it to be fast. You can buy local crafts in the villages and at the Mekong Elephant Park in Pak Beng, so it’s wise to bring cash.

Thailand

The Four Seasons Tented Camp Golden Triangle (tents from $5,000 for two nights, all-inclusive) is a short speedboat ride from where the Gypsy stops. Rescued and adopted elephants roam the property. Chiang Rai, 45 minutes away by taxi, is the nearest airport.

Source: travelandleisure.com